There have been different versions.

Their conversation is a little over half an hour long but the amount of information and insights contained would take far longer to fully unpack. This writing, to which I am not laying any claim, is what I found to be the important points. Hopefully, this synopsis correctly conveys the pertinent facts and authentically retains their expressed perspectives.

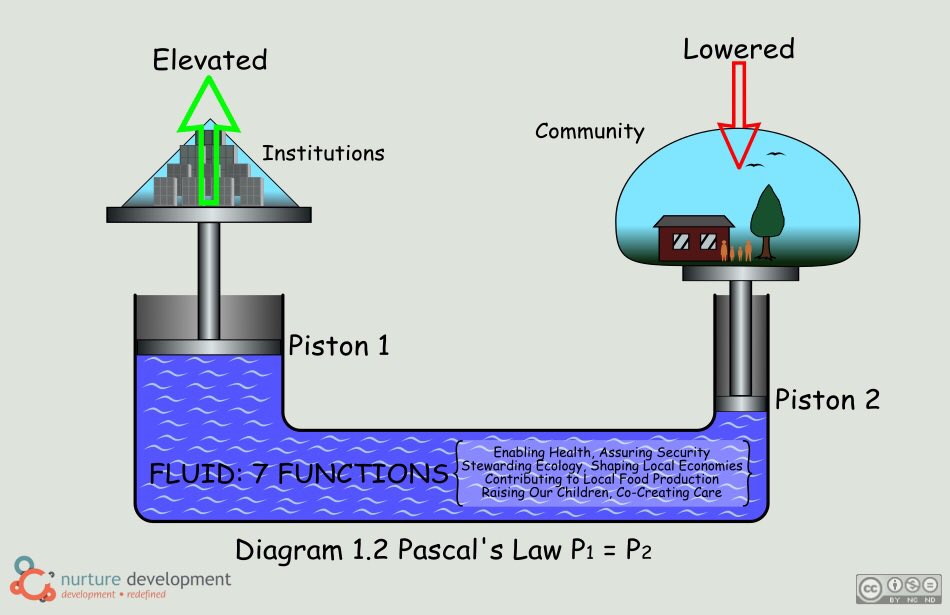

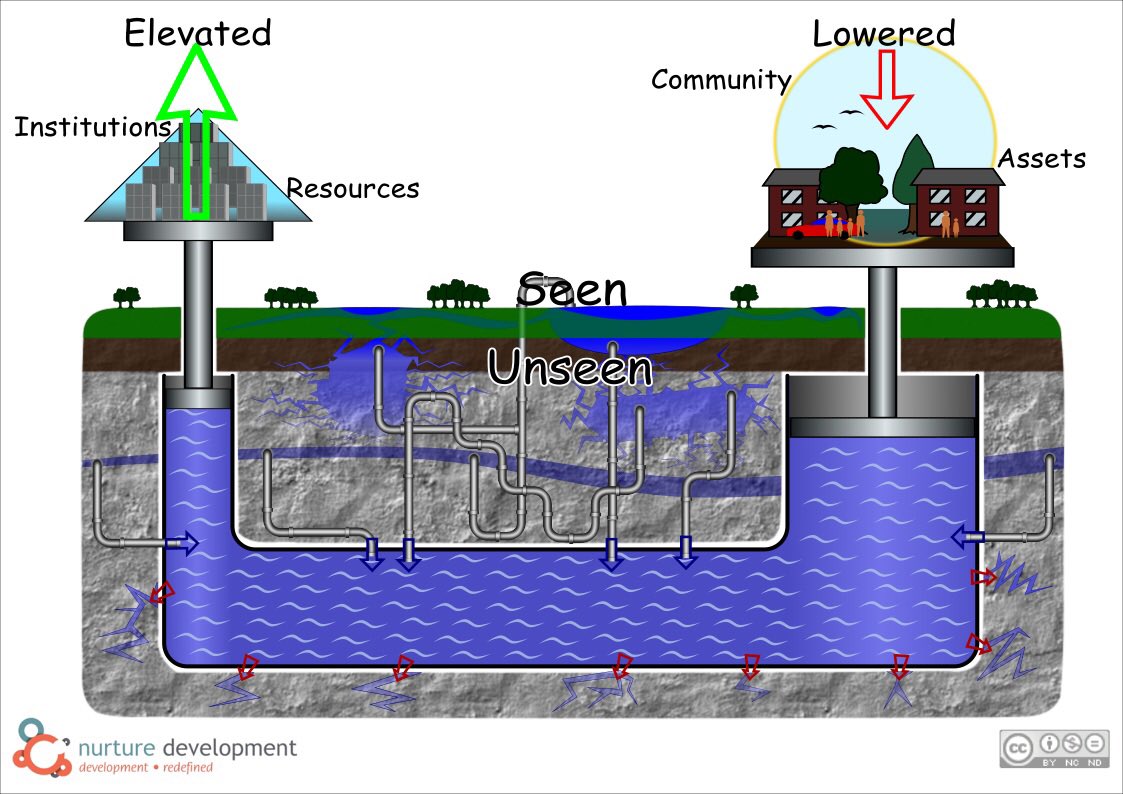

The basic idea as presented by Cormac and John is that a hydraulic mechanism in its simplest form is a closed system, pushing down on one part of the mechanism another part has to go up by necessity. Similarly, as a community is performing its functions and institutions are performing their functions, if you push down on one then the other will go up and if you push on the other the reverse happens through processes largely unseen and often not understood. The hydraulic relationship provides an important insight in terms of the power, asymmetry of power dynamics between communities and institutions.

The image is further meant to convey a concept to which should be easily attested, that people know that in most neighborhoods people are not as connected as they would have been 50 years ago and raises the question, why and what are the ramifications?

Cormac and John provide examples of components of community life, education, public safety, and health that have been expropriated by institutions or appropriated by them through the acquiescence of communities, invariably implicit as nobody votes for it. Bringing people to think that more police equals more safety or that more hospitals equal more health.

The state of the educational systems in the US can be explained to a great extent by the multiple community functions taken over by schools. Eighty-five functions since 1900 according to the book, ”Schools Can't Do it Alone.” The educational institutions have been expropriating community functions that have fallen mainly on the shoulders of teachers, a clearly crushing responsibility at which they are doomed to fail.

Police Departments are struggling with the problem of not having the members of the community involved, as though they had nothing to do with the issue of security and safety. More enlightened Police Departments have come to understand that the connection isn't simply about getting the community to call the police and report on their neighbors. There is a very clear community function around the production of safety. It is an association or function of community life itself. Neighborhood policing has become much more about community building and less about enforcement and informing.

At the same time, Police Departments and other institutional entities are still defining themselves and justifying ever increasing budgets by consistently saying we need more money to deal with all these different problems.

Medical practitioners cite similar relationships in health to those around education and safety with eighty-five percent or even higher of what determines well-being having nothing at all to do with clinical or pharmacological intervention or anything that a medical professional can do to us. Most of what counts for the healing of suffering happens outside the medical institutional realm. One primary care doctor, a public health practitioner who runs a primary care facility said that forty-five percent of the people who come into his surgery is not biomedically ill. They're lonely, disconnected in some way. A word for their condition is isolated, they are in a sense alone. Perhaps they have some moderate challenges in socializing but technically they're not sick. They need commune they don't need a doctor.

The growth of loneliness in modern societies has been increasing even though we see ourselves in cities as all collective. Our loneliness, according to Cormac has been growing as we left the more rural areas. In Vancouver, Canada a foundation gave a list of about 40 issues and asked residents to rate them and the number one issue was not crime or education but loneliness. What we're seeing now is the rise of programmatic interventions around loneliness. Loneliness has now become the new pathology that is being targeted with programs by institutions.

This erosion has come through the evolution of consumerism. It is a shift to an idea of a consumer society in which one could buy what one wants to be produced, being individuals who took that responsibility out of our community and put it into the marketplace. It's the consumer economy built on the assumption that we can outsource these at one-time community functions to the institutional realm so that we can get on with being consumers.

Marketing and media, over and over again, are trying to persuade us that it is better to buy a life than it is to live one. Advertising things that will be done for money that we would never have seen in the past done for money.

We now turn to institutions to buy through taxes and charitable donations solutions for the issues we face collectively but that shift in culture is problematic because so many of those functions are ones that only people in face-to-face relationships with each other can really perform effectively.

We have been handing over functions at which we are most competent and most capable to perform. The institutions are appropriating all of these new functions, yet they are overburdened and are less able to do their actual legitimate functions becoming a collective equivalence, as Cormac noted, of the Peter Principle where institutions are elevated to their own level of incompetence.

City leaders, responsible for dealing with these issues want their residents to see local government as trustworthy and know that it can be relied on but all too often in their minds the role of the citizen is defined as that which happens after the important work of the professionals is completed. This is a perfect example of a hydraulic relationship. The role of the professionals goes up, the role of the citizens goes down. This is an inversion of democracy for it needs to be the case that the role of the professional is what happens after the important work of the citizen is complete.

Cormac and John then asked how does the institutional realm lead by stepping back? How do we locate some of that appropriated authority back into community life again? How can we resurrect the community in taking on the functions that are the strength of the social contract of neighborhoods in our towns?

John thought of it as being almost forceful in nature on many institutional leaders because of their accountability and defining trustworthiness. That what they could do is get folks, people in our communities, to see that our institutional people, in our schools, at our police departments or hospitals, are at their limits, in truth over their limits, and are becoming counterproductive because of all the functions we have given them.

The alternative is stepping forward into our own power, our collective cultural power with the agreement that through social contract there are certain things teachers, police officers, and healthcare professionals are not going to do. Responsibilities that we decide to take back as community.

Cormac and John also provide three successful examples of taking back responsibility for collective functions of, by, and for the community.

The manager of a large housing development in Sweden sent out an invitation saying if are you lonely come next Tuesday to the dining room and we'll have lunch together had eighty-some people show up. The manager was able to succeed because he had support from community builders in the neighborhood in addition to connectors who were also at that lunch, as well as welcomers and askers in the neighborhood.

Another example Cincinnati Starfire, a workshop placement for people with intellectual disabilities that reimagined its role through its participants and became an enterprise space where local small businesses pay rent and establish small pop-up offices in which they operate. More importantly, participants are also out in their own neighborhoods with resources and money that they can spend effectively becoming community builders who are contributing to their neighborhoods. The professional staff is also out in the neighborhoods with them, supporting them, supporting relationship building so they too are core community builders.

Then there was Henry Moore, the assistant city manager of Savannah Georgia who sent a letter to the people in the lowest income neighborhood asking them to write a letter no more than one page saying what they would like to do to improve their block and have two other people sign it who will also do it with a maximum grant of $100. The first year he got eighty requests with very little money spent. From an institutional point of view, it was one of the most incredible ways of beginning the change of the hydraulics system. He was saying to the community, you have all kinds of functions that you can perform. How do we support you? He also said We (the City) are not going to do work, the community took up the challenge and they did they work. In the past, investment had been put in from the top through Community Block Grants. ”When I had the block grants that made almost no change but when I led by stepping back and provided the incentive for citizens to be producer things changed”.

Below is the Kumu presentation looking at the same subject from a Systems Thinking perspective.

The next post will examine some of the differences.